Introduction to the Compose Snapshot system

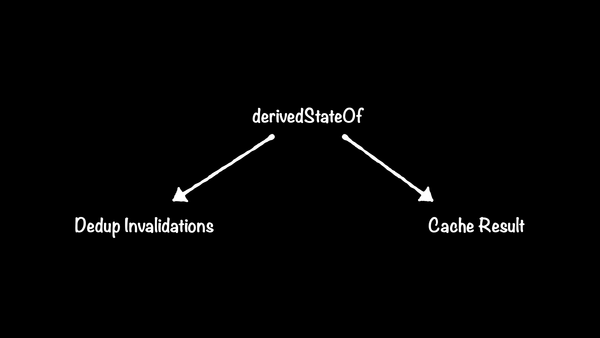

Jetpack Compose introduces a novel way to handle observable state. For an introduction that adds some historical context about reactive programming on Android, see the prequel to this post, A historical introduction to the Compose reactive state model. This post explores the lower level snapshot APIs. A lot of the stuff here has some pretty deep academic/computer science roots, but this isn’t a dissertation so I’m going to come at it from a more pragmatic angle. I might do another post in the future that looks at the implementation of the snapshot machinery under the hood, which is even more complex and probably too much content to reasonably fit into this post anyway—until then, check out my talk Opening the shutter on snapshots for that info.

State in Compose

In Compose, any state that is read by a composable function should be backed by a special state object returned by functions like these:

mutableStateOf/MutableStatemutableStateListOf/SnapshotStateListmutableStateMapOf/SnapshotStateMapderivedStateOfrememberUpdatedStatecollect*AsState

Basically, anything that implements the State<T> interface (including MutableState<T>) or the StateObject interface (which the built-in implementations of MutableState actually do as well, if you look deep enough). If you’re wondering why I didn’t mention remember, take a few minutes to go read this post explaining the difference.

The primary reason for using snapshot state objects to hold your state, or at least the first one you’ll probably come across when learning Compose, is so that your composables will automatically update when that state changes. Another reason that is just as important but not discussed as often is so that changes to composable state from different threads (for example, from LaunchedEffects) are appropriately isolated and can be performed in a safe manner, without race conditions. It turns out both these reasons are related.

Note on terminology: I’ll be using the term “snapshot state” or “state value” to refer to things like

MutableStates. The term “snapshot state” appears in the Compose source and documentation. The reason why will hopefully be apparent by the end of this post!

Keep in mind that most of the APIs introduced below are not intended to be used by everyday code. You don’t need to even know about any of them to use Compose. A lot of these APIs are easy to mess up and get yourself in trouble – for example, a lot of them require explicitly disposing various handles. They are useful for building higher-level concepts on top of, such as the snapshotFlow function, or the glue code that the Compose runtime uses to trigger recomposition, but it’s very unlikely you’d ever need to reach for them if you’re building apps. Nevertheless, it is useful to see how these low-level building blocks work so that you can reason about the higher-level ones and are more prepared to go read the Compose source if you ever have the need or inclination to do so.

The “snapshot”

Compose defines a type called Snapshot and a bunch of APIs for working with them. A Snapshot is a lot like a save point in a video game: it represents the state of your entire program at a single point in history. Well, that’s not entirely true – it represents the state of all the snapshot state values that existed in your program when it was taken, so for the sake of keeping the explanation simple let’s assume all your state is in snapshot states. Any code can take a snapshot – these are public APIs.

To help illustrate, I’ll introduce the example of a simple Dog class and a main function that performs some operations on it. Dogs support snapshots because their names are stored in MutableState objects.

class Dog {

var name: MutableState<String> = mutableStateOf(“”)

}

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = “Spot”

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeSnapshot()

dog.name.value = “Fido”

// When finished with the snapshot, it must always be disposed.

// Subsequent examples omit this step for brevity, but don’t

// forget to do it if you copy and paste any of this code!

snapshot.dispose()

}

Notes on examples

I’ll use explicit

MutableStateproperties in the example code, without property delegation (thebysyntax), to make the code more clear.Most of the example content is in

mainfunctions. If you’re trying to run these yourself, you can copy and paste the code into JUnit test functions for easy running from an IDE. However, the snapshot system, while shipped as part of Compose, is independent from and does not require other Compose features, so theoretically they should be runnable as regular command-line programs.

“Restoring” snapshots

What good is a save point if you can’t restore it? In a similar way, snapshots can be restored - kind of. You can’t overwrite the current state of the world. Instead, you give the snapshot a function (i.e. a lambda) to run. The snapshot will run the function, and inside the function all the state values will have the value they were snapshotted with.

Let’s try changing our dog’s name and reading the initial one from the snapshot.

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = “Spot”

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeSnapshot()

dog.name.value = “Fido”

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot.enter { println(dog.name.value) }

println(dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

Fido

Spot

Fido

If that doesn’t seem impressive, remember that takeSnapshot() will take a snapshot of all the state values in your program, no matter where they were created or set. The enter function will temporarily restore the snapshot states to all code in the function, even if it has a deep call stack:

fun main() {

// …

snapshot.enter { reminisce(dog) }

}

private fun reminisce(dog: Dog) {

printName(dog.name)

}

// MutableState<T> extends the interface State<T>

private fun printName(name: State<String>) {

println(name.value)

}

So far all we’ve done is read snapshotted data though. Real programs change data, so how do we do that?

Mutable snapshots

Let’s try changing our dog’s name inside that enter block:

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeSnapshot()

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot.enter {

println(dog.name.value)

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println(dog.name.value)

}

println(dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

Spot

java.lang.IllegalStateException: Cannot modify a state object in a read-only snapshot

Snapshots created with takeSnapshot() are read-only. Inside the enter block, we can read back the snapshotted values, but we can’t write to them. We need a different function to create a mutable snapshot: takeMutableSnapshot(). This function returns an instance of a MutableSnapshot, which is just like a Snapshot, but it has some extra powers. It also has an enter method, but its enter method can modify state values.

Let’s fix our crash:

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot()

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println(dog.name.value)

}

println(dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

Spot

Fido

Spot

No crash! But wait – even after changing the name in the enter block, the change is reverted as soon as enter returns. Snapshots don’t only allow you to peek into the past, they also allow you to isolate changes and prevent them from affecting anything else. But what if we want to “save” those changes? We need to “apply” the snapshot.

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot()

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println(dog.name.value)

}

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot.apply()

println(dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

Spot

Fido

Spot

Fido

Voila! After calling apply() the new value is visible outside the enter block! The pattern of taking a mutable snapshot, running a function on it, and then applying it is so common there’s a helper function that handles the boilerplate for us: Snapshot.withMutableSnapshot(). We can simplify the above example like this:

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

Snapshot.withMutableSnapshot {

println(dog.name.value)

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println(dog.name.value)

}

println(dog.name.value)

}

Let’s recap. So far we can:

- take snapshots of all our state,

- “restore” those snapshots for a particular block of code, and

- change state values.

We still haven’t seen how to actually observe changes though. Let’s figure that out next.

Tracking reads and writes

Observing changes to state using an observer pattern is a two part process. First, the parts of the code that depend on the state register change listeners. Second, when the value changes, all registered listeners are notified. Manually registering observers, and remembering to unregister them, can be error prone. Compose state helps out here by letting you register observers on state read - without any explicit function call! For example, when the code reading the state is a composable function, the Compose runtime updates it by recomposing the function.

The takeMutableSnapshot() function actually has a couple optional parameters. It takes a “read observer” and a “write observer” – both are simple (Any) -> Unit functions that will be called any time a snapshot state value is read or written, respectively, inside an enter block. What you do with these values is really up to you, although since the values could be literally anything, you can’t really do much. One thing you can do is simply to track all the values read from the snapshot in some data structure so that you can register a change listener in the future and determine whether any changed values are ones that you previously read, although Compose includes a helper class to do that for you (see below).

Let’s see if our dog’s name is accessed:

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val readObserver: (Any) -> Unit = { readState ->

if (readState == dog.name) println("dog name was read")

}

val writeObserver: (Any) -> Unit = { writtenState ->

if (writtenState == dog.name) println("dog name was written")

}

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot(readObserver, writeObserver)

println("name before snapshot: " + dog.name.value)

snapshot.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println("name before applying: ")

// This could be inlined, but I've separated the actual state read

// from the print statement to make the output sequence more clear.

val name = dog.name.value

println(name)

}

snapshot.apply()

println("name after applying: " + dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

name before snapshot: Spot

dog name was written

name before applying:

dog name was read

Fido

name after applying: Fido

We can see that the MutableState instance stored in the dog.name property gets passed to our read and write observers. The observers are invoked immediately when the value is accessed too – note in the above output that “dog name was read” is printed before the actual name.

Another advantage of snapshots is that state reads are observed no matter how deep in the call stack they occur. This means you can factor code that reads state out into functions or properties, and those reads will still be tracked. The property delegate extensions on the State types rely on this. To prove it, we can add some indirection to our example and see that the reads are still reported:

fun Dog.getActualName() = nameValue

val Dog.nameValue get() = name.value

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val readObserver: (Any) -> Unit = { readState ->

if (readState == dog.name) println("dog name was read")

}

val snapshot = Snapshot.takeSnapshot(readObserver)

snapshot.enter {

println("reading dog name")

val name = dog.getActualName()

println(name)

}

}

// Output:

reading dog name

dog name was read

Spot

State changes are de-duplicated. If a state value is set to the same value, no change is recorded for that value. The logic that defines what values are considered “equal” can actually be customized via a policy, as we’ll see later in this post when we examine conflicting snapshot writes.

SnapshotStateObserver

The pattern of tracking all the reads in a particular function and then executing a callback when any of those state values is changed is so common that there’s a class that implements it for us: SnapshotStateObserver. The usage of the class looks something like this:

- Create a

SnapshotStateObserverand pass in a function that acts as a Java-styleExecutorto run change notification callbacks. - Call

start()to start watching for changes. - Call

observeReads()one or more times, passing it a function to observe reads from as well as a callback to execute when any of the read values is changed. Every time the callback is invoked, the set of states being observed is cleared andobserveReads()must be called again in order to continue tracking changes. - Call

stop()andclear()to stop watching for changes and release resources required to do so.

This is a bit of a longer example, but shows how we can observe state changes to our dog’s name using SnapshotStateObserver:

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

fun immediateExecutor(runnable: () -> Unit) {

runnable()

}

fun blockToObserve() {

println("dog name: ${dog.name.value}")

}

val observer = SnapshotStateObserver(::immediateExecutor)

fun onChanged(scope: Int) {

println("something was changed from pass $scope")

println("performing next read pass")

observer.observeReads(

scope = scope + 1,

onValueChangedForScope = ::onChanged,

block = ::blockToObserve

)

}

dog.name.value = "Spot"

println("performing initial read pass")

observer.observeReads(

// This can be literally any object, it doesn't need

// to be an int. This example just uses an int to

// demonstrate subsequent read passes.

scope = 0,

onValueChangedForScope = ::onChanged,

block = ::blockToObserve

)

println("starting observation")

observer.start()

println("initial state change")

Snapshot.withMutableSnapshot {

dog.name.value = "Fido"

}

println("second state change")

Snapshot.withMutableSnapshot {

dog.name.value = "Fluffy"

}

println("stopping")

observer.stop()

println("third state change")

Snapshot.withMutableSnapshot {

// This change won't trigger the callback.

dog.name.value = "Fluffy"

}

}

// Output:

performing initial read pass

dog name: Spot

starting observation

initial state change

something was changed from pass 0

performing next read pass

dog name: Fido

second state change

something was changed from pass 1

performing next read pass

dog name: Fluffy

stopping

third state change

For more information on SnapshotStateObserver and restartable functions in general, check out Restartable functions from first principles.

We’re still missing a critical component though – snapshot state values can be changed anywhere, not just inside snapshots. Remember back to our initial sample – we can change the name directly in the main function, and so there must be a way to observe those “top-level” writes, right?

Nested snapshots

Well, it turns out that all code actually runs in a snapshot – even if there’s no explicitly-created snapshot around it. Snapshots have one other feature that we haven’t covered yet: they nest. If you call takeMutableSnapshot() inside the enter block of a different snapshot, then when the inner snapshot is applied it will only be applied to the outer snapshot. The outer snapshot must then be applied in turn in order for the changes to continue to propagate up the snapshot hierarchy, and so on up the tree, until the changes are applied to the root snapshot. This root snapshot is called the “global snapshot”, and it’s always open. The global snapshot is a bit of a special case, so before we talk about that, let’s explore snapshot nesting.

Let’s create a nested snapshot called innerSnapshot to rename our dog in and see what happens:

Fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val outerSnapshot = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot()

println("initial name: " + dog.name.value)

outerSnapshot.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println("outer snapshot: " + dog.name.value)

val innerSnapshot = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot()

innerSnapshot.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fluffy"

println("inner snapshot: " + dog.name.value)

}

println("before applying inner: " + dog.name.value)

innerSnapshot.apply().check()

println("after applying inner: " + dog.name.value)

}

println("before applying outer: " + dog.name.value)

outerSnapshot.apply().check()

println("after applying outer: " + dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

initial name: Spot

outer snapshot: Fido

inner snapshot: Fluffy

before applying inner: Fido

after applying inner: Fluffy

before applying outer: Spot

after applying outer: Fluffy

Notice the last two lines – the rename to “Fluffy” was not applied to the top-level value until we applied the outer snapshot. This makes sense if you think of applying a snapshot as a state mutation operation. Since state mutations inside snapshots aren’t applied until apply() is called, nested snapshots’ applications are just another type of mutation operation that isn’t visible until the outer snapshot is applied.

The global snapshot

The global snapshot is a mutable snapshot that sits at the root of the snapshot tree. In contrast to regular mutable snapshots, which must be applied to take effect, the global snapshot does not have an “apply” operation – there’s nothing to apply it to. Instead, it can be “advanced”. Advancing the global snapshot is similar to atomically applying it and immediately reopening it – change notifications are sent for all snapshot state values that were modified in the global snapshot since the last advance.

There are three ways to advance the global snapshot:

- Apply a mutable snapshot to it. In the above example, when

outerSnapshotis applied, it’s applied to the global snapshot, and the global snapshot is advanced. - Call

Snapshot.notifyObjectsInitialized. This sends change notifications for any state values that were changed since the last advance. - Call

Snapshot.sendApplyNotifications(). This is similar tonotifyObjectsInitialized, but only advances the snapshot if anything actually changed. This function is implicitly called in the first case, whenever any mutable snapshot is applied to the global one.

Because the global snapshot is not created by a takeMutableSnapshot call, we can’t pass in read and write observers like normal. Instead, there’s a dedicated function to which installs a callback for when state changes are applied from the global snapshot: Snapshot.registerApplyObserver().

Let’s use registerApplyObserver and sendApplyNotifications to rename our dog without an explicit snapshot:

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

Snapshot.registerApplyObserver { changedSet, snapshot ->

if (dog.name in changedSet) println("dog name was changed")

}

println("before setting name")

dog.name.value = "Spot"

println("after setting name")

println("before sending apply notifications")

Snapshot.sendApplyNotifications()

println("after sending apply notifications")

}

// Output:

before setting name

after setting name

before sending apply notifications

dog name was changed

after sending apply notifications

The Compose runtime uses the global snapshot APIs to coordinate snapshots with the frames it is responsible for drawing for your UI. When something changes a snapshot state value outside of a composition (e.g. a user event like a click fires an event handler that mutates some state), the Compose runtime schedules a sendApplyNotifications call to happen before the next frame is drawn. When it’s time to generate the frame, the sendApplyNotifications call advances the global snapshot and applies any changes made to it. The resulting change notifications sent from the global snapshot are used to determine which composables need to be recomposed. Compose then takes a mutable snapshot, recomposes those composables inside that snapshot, and finally applies the snapshot. That snapshot application advances the global snapshot again and makes any state changes performed during recomposition visible to code running in the global snapshot – including code running in other threads.

Multithreading and the global snapshot

The global snapshot has important implications for multithreaded code. It is not uncommon to run code on a background thread without using explicit snapshots. Consider a network call made from a LaunchedEffect on the IO dispatcher that updates a MutableState with the response. This code mutates a snapshot state value, without a snapshot, in a background thread (remember: Compose only wraps compositions in snapshots, and effects are executed outside of compositions). Without snapshots, this would be dangerous – any code reading that state on other threads would see the new value immediately, and if the value changed at the wrong time, could cause a race condition. However, snapshots have a property called “isolation”.

Within a snapshot on a given thread, no changes made to state values from other threads will be seen until that snapshot is applied. Snapshots are “isolated” from other snapshots. If code needs to operate on some state and wants to ensure that no other threads can mess with it in the meantime, typically that code would use something like a mutex to guard access to its state. However, because snapshots are isolated, it can just take a snapshot instead, and operate on the state inside the snapshot. Then, if other threads mutate the state, the thread with the snapshot will be blissfully unaware of the changes until the snapshot is applied, and vice versa. Any changes made to state inside the snapshot will not be visible to other threads until the snapshot is applied and the global snapshot is automatically advanced.

But what about code running on other threads without an explicit snapshot? That code will immediately see changes from other threads if they decide to apply their snapshots. In database terms, the snapshot system trades consistency for availability. Code that needs consistency needs to take snapshots, but in most cases snapshots can be ignored.

Conflicting snapshot writes

In the examples up to now we’ve only been taking a single snapshot, but there’s no reason we couldn’t take a few. After all, if Compose is using snapshots to run code in parallel on multiple threads, it’s going to need multiple snapshots.

Let’s try taking a few mutable ones and mutating the name concurrently (we’re still doing everything in a single thread, but the snapshot operations and state mutations are interleaved):

fun main() {

val dog = Dog()

dog.name.value = "Spot"

val snapshot1 = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot()

val snapshot2 = Snapshot.takeMutableSnapshot()

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot1.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fido"

println("in snapshot1: " + dog.name.value)

}

// Don’t apply it yet, let’s try setting a third value first.

println(dog.name.value)

snapshot2.enter {

dog.name.value = "Fluffy"

println("in snapshot2: " + dog.name.value)

}

// Ok now we can apply both.

println("before applying: " + dog.name.value)

snapshot1.apply()

println("after applying 1: " + dog.name.value)

snapshot2.apply()

println("after applying 2: " + dog.name.value)

}

// Output:

Spot

in snapshot1: Fido

Spot

in snapshot2: Fluffy

before applying: Spot

after applying 1: Fido

after applying 2: Fido

Both enter blocks saw their modified value internally, and the first snapshot successfully applied its change, but after applying the second snapshot the name was still “Fido”, not “Fluffy”. To understand what’s going on here, let’s take a closer look at the apply() method. It actually returns a value of type SnapshotApplyResult. It’s a sealed class that can either be Success or Failure. If we add print statements around the apply() calls, we will see that the first one succeeds, but the second fails. The reason is that there’s an unresolvable conflict between the updates – both snapshots are trying to change the same name value based on the same initial value (“Spot”). Because the second snapshot was executed with the name of “Spot”, the snapshot system can’t assume that the new value, “Fluffy”, is still correct. It either needs to re-run the enter block after applying the new snapshot, or be told explicitly how to merge names. It’s the same situation as when you’re trying to merge a git branch that has conflicts – the merge will fail until you resolve the conflicts.

Compose actually has an API for resolving merge conflicts! mutableStateOf() takes an optional SnapshotMutationPolicy. The policy defines both how to compare values of a particular type (equivalent), as well as how to resolve conflicts (merge). Some policies come out of the box:

structuralEqualityPolicy– Compares objects by using theirequalsmethods (==), all writes are considered non-conflicting.referentialEqualityPolicy– Compares objects by reference (===), all writes are considered non-conflicting.neverEqualPolicy– Treats all objects as unequal, all writes are considered non-conflicting. This should be used, for example, when the snapshot holds an mutable value and this is used to indicate that the value changed in a way not detectable by == or ===. Holding a mutable object in a mutable state object is not safe (as the mutations are not isolated in any way) but useful if the object implementation is not in your control.

Notice that none of the pre-built policies resolve write conflicts. Conflict resolution is highly use-case-specific, so there’s no reasonable default. On the other hand, sometimes conflicts can be resolved trivially: the method documentation for the merge method includes the example of a counter. If a counter is incremented by two snapshots independently, the merged counter value is the sum of the amounts by which the counter was incremented in both snapshots.

In our example, it doesn’t really make sense to merge names, so instead let’s just include the previous name in the new one:

class Dog {

var name: MutableState<String> =

mutableStateOf("", policy = object : SnapshotMutationPolicy<String> {

override fun equivalent(a: String, b: String): Boolean = a == b

override fun merge(previous: String, current: String, applied: String): String =

"$applied, briefly known as $current, originally known as $previous"

})

}

fun main() {

// Same as before.

}

// Output:

Spot

in snapshot1: Fido

Spot

in snapshot2: Fluffy

before applying: Spot

after applying 1: Fido

after applying 2: Fluffy, briefly known as Fido, originally known as Spot

If the application of a snapshot results in a write conflict that can’t be resolved, the apply operation is considered failed. The only thing left to do at that point is to take a new snapshot and retry the change.

Conclusion

Compose’s snapshot system powers some of the key features of its design:

- Reactivity: Stateful code is always kept up-to-date, automatically. You don’t need to worry about tracking invalidations or subscriptions – not only as a feature developer, but even as a library developer. You can make your own “reactive” components using snapshots without manually adding dirty flags.

- Isolation: Stateful code can operate on state without worrying about that state being changed out from under it by code running on different threads. Compose can take advantage of this to do tricks that the old View toolkit couldn’t, such as fan out recompositions onto multiple background threads.

And it does all this using plain old Kotlin features – there is no compiler magic involved. Compose does include a compiler plugin, but that plugin is used for other stuff. The snapshot system uses ThreadLocals under the hood, which are a standard concept from Java that have been around for a long time. I might explore how they’re used in a follow-up post, so stay tuned!

If you want to play with the snapshot system without using the rest of Compose, all you need to do is add a dependency on the runtime artifact:

implementation("androidx.compose.runtime:runtime:$composeVersion")

Hopefully this pulls the curtain back just far enough that you can start to see how mutableStateOf works together with the rest of the Compose infrastructure to monitor and react to state changes. Please let me know if you have any further questions in the comments!

Further reading

If you'd like to learn more about how the actual snapshots algorithm works, I've given a talk called Opening the shutter on snapshots that goes into lots of detail and explains them with lots of diagrams.

Unfortunately, at the time of this writing, there isn’t much official documentation about this part of Compose. The closest thing I could find is the “Jetpack Compose Compilation” episode of the official Android podcast, Android Developers Backstage, where Leland and Adam discuss some of the snapshot workings.

The best way to learn how any code works is to read the code. The Compose source code is generally very clean and well-commented, so it’s a really great place to start. There’s a lot more to dig into – this post only covers a subset of the public API for snapshots. Most of the API is in the Snapshot.kt file, so that’s a good place to start exploring on your own. If you want to see how some of this API is used in practice, checkout the implementation of snapshotFlow.

If you really want to dig deep into the theory behind this stuff, here’s a few more leads:

- You could start with the Wikipedia article on multiversion concurrency control (MVCC). Compose’s snapshot system is an implementation of MVCC. MVCC is usually discussed in the context of databases, but, as the article points out, it also applies to state stored in volatile memory, which is really a kind of database if you squint hard enough.

- There’s also a comment in the

Snapshotcode linking to a PDF of the paper “Rethinking serializable multiversion concurrency control”. - The counter example mentioned above is an example of something called a “conflict-free data type”, which you can read more about here.

Also, check out my other articles about Compose state.

Thanks to Mark Murphy, Matt McKenna, and Adam McNeilly for reviewing this post and providing early feedback, and to Chuck Jazdzewski and Sean McQuillan for providing extensive technical corrections and teaching me a bunch in the process!